Today obviously is the Sunday of Icons, also known as Sunday of the true faith, or Sunday of Orthodoxy. It commemorates the final restoration of sacred images in the churches on the first Sunday of Lent in 843 in the Eastern Roman Empire. The procession recalls when the people, monks, and nuns carried icons that had been hidden during the persecutions and destruction of holy images into their parish churches to be used again in prayer. The heresy of iconoclasm, of breaking sacred images, was rooted in the denial of the incarnation, that God became Man, one of the central teachings in Islam. To this day you can go in old churches in Turkey or in territories that used to be ruled by the Turks in Europe and see how the Muslim warriors scratched out the faces on frescoes of the saints or shot up statues and icons.

We know that Nazareth was a small town, home to a completely Jewish population. Archaeology shows that the Jews of Nazareth in the first century kept to the strict orthodox rules regarding food and lifestyle. But as the Pharisees pointed out to Nicodemus in denying that Jesus was a prophet, there were absolutely no writings about anyone wonderful coming out of Galilee. The region was mixed with Jews and Greeks and other pagans, a bustling commercial area but with no religious significance at all. Nathaniel asks a logical question of Philip – how can anything good come from Nazareth?

Jesus answered, “Before Phillip called you, when you were under the fig tree, I saw you.” Sitting under a tree was not just something people did when they found shade in the heat of the day. Sitting under a fig tree was a particularly important thing to do when one was praying, or thinking deep thoughts. The fig tree was a symbol of God’s blessing and peace. It provided shade from the midday sun and a cool place to retreat and pray. The leaves are large, and an old fig tree can be quite large, protecting a substantial patch of ground and providing a protected space in which to pray or teach or just sit and think. Whatever it was that Nathaniel was pondering underneath that tree, it had to be something very important, because when Jesus says I saw you under the fig tree, he reacts with that powerful statement, Truly you are the son of God! He makes a gigantic leap of faith, not because he realizes not that Jesus could see him sitting under a particular tree, but rather that Jesus knew what was happening in his soul.

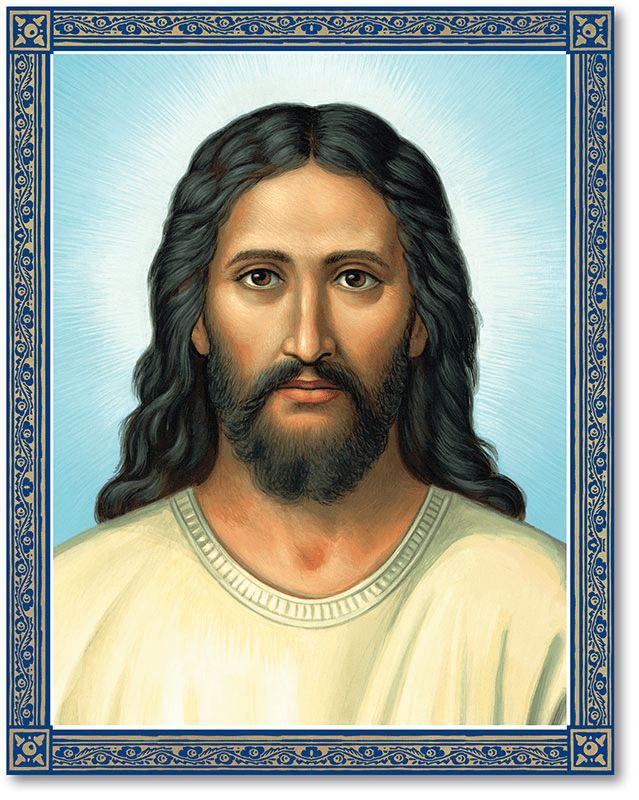

Christ sees us. In icons, the eyes are among the most prominent feature. Look up at the fresco on our ceiling – Jesus is looking down at us. In the window on the south side, he is looking out at us. In the icon of Christ the Teacher on the iconostas, he is looking straight out at us. Jesus sees us – God sees us. Think of the compassion in the eyes of Jesus; for these are the eyes through which God looks at us today. What compassion must have shown in His eyes when, looking at Jerusalem, He wept over it. What compassion must have shown in His eyes when He healed the sick and when He wept before the tomb of Lazarus, His friend.

People can look at someone else with hardness, gentleness, even indifference. Or we can look at someone and see beyond their body and notice something within them. This is the way God looks at us, and not just to see us, but to affect us. Jesus looked at the rich young man who was consumed with owning stuff, looked at him with love, but let him walk away when he wouldn’t get rid of the stuff. Jesus looked at the blind, the crippled, the sick, the lepers, the suffering and had compassion. Jesus looked and he truly saw into people, just like he does with Nathaniel. And Nathaniel also sees in a different way – he meets Jesus, and goes far beyond what Philip or Andrew or Simon could do – he is able to proclaim the truth of the Incarnation. “You are the Son of God.”

Icons can be made because of the Incarnation – Jesus was flesh and blood as well as divine, and therefore people truly met him, truly experienced him, truly encountered him. He was not a ghost, he was not some vague demigod, he was and is the Son of God as well as the Son of Mary. Christians have rooted all of their religious art in the reality of the incarnation, as is made clear in the teachings of the ecumenical councils that defined that mystery and that defended the making and veneration of icons. My experience has been that those who usually attack the use of sacred images tend to have a pretty limited vision of Jesus Himself. The Muslims deny the incarnation of God in Christ even while admitting the virginal conception of Jesus in the womb of Mary. The Jews believe that no one can depict the divine, and in that sense they’re right because no one can adequately paint God. But Christians should be able to depict the Lord, and therefore the Virgin and saints, because it is both an affirmation of the Incarnation and of the goodness of God’s created world and the elements inside it.

We are meant to not only pray with icons, but allow ourselves to use icons so as to see God, try to understand God better, let ourselves be opened to God’s mercy and grace. Philip proclaims to Nathaniel, “Come and see!” And Nathaniel does come, and does see, and sees far more than Philip had seen. This is our job as Christian people, as members of the true faith, as faithful participants in Catholic life, to come and see and to invite others to come and see. People think more about God during Lent, even those who are routinely indifferent to religious practice. The sudden prevalence of fish sandwiches at Blake’s and MacDonald’s as “spring specials” or “seasonal meals” make people wonder and then say, Oh yeah, it’s Lent. Take the opportunity to invite someone this year to worship with you. Use your icons at home to see God differently, to look at the large profound eyes of Jesus in an icon and see Him in a new way. Ask the Lord tonight and every day this week, help me to see you and recognize you more deeply this Lent. Make it a Lent that will be a Lent to remember, a Lent to be transformed during, a Lent to be made whole in.

Christ is among us.

Leave a comment